At the heart of Emily Sargent: Portrait of a Family, an exhibition now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, lies a question which, in the not-too-distant past, seemed new, and yet now seems somewhat dated: What might have become of Emily Sargent if she—a woman of late-19th century America—had enjoyed the same opportunities as her eternally celebrated brother, John Singer Sargent? What if the playing field had been level? Looking at Emily’s watercolors, many of which were done side by side with her brother, some of which they worked on together, a somewhat different observation arose: How great a watercolorist—and painter, in general—might John Singer Sargent have become, had he not expended so much energy painting staid portraits of the Gilded Age rich and famous?

Emily Sargent (1857-1936), Alhambra, 1903. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 10 x 14 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous gift, at the request of members of the artist’s family, 2021 (2121.110.16).

Certainly, Sargent’s portraits made his name and fortune in his lifetime, and early portraits such as those of Madame X and Robert Louis Stevenson transcend the genre, but he himself came to loathe the whole commission process. Later in life, he confined himself to charcoal portraits—they were quick and required far less commitment.

Emily, of course, receded into her brother’s shadow, even though they continued to meet and paint together on occasion. Her body of work, unlike his, was left largely unseen. Until, that is, the recent discovery of her watercolors in 1998, when a family member discovered some 440 of her paintings in a trunk. In 1922, the family divided part of Emily Sargent’s oeuvre among a number of museums in the United States and the United Kingdom. With the remainder, they hope to establish a scholarly center named for their all-but-forgotten ancestor.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), Spanish Midday, Aranjuez, 1903. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper 10 x 14 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.81h).

Emily Sargent was born in 1857; John a year earlier, both in Florence, Italy. After their mother, Mary, lost her first child, their father, an eye surgeon, took her abroad. Though based in Paris, the Sargents would live a nomadic, expatriate life in Europe, a life that would provide the kind of education of the eye that every artist craves. Emily’s mother was herself an artist—one of her drawings is in the exhibition—and she encouraged all her children to draw and paint. At the age of 4, Emily suffered a spinal injury which would require attention for the rest of her life, though she never let that stop her from traveling and painting.

What the exhibition is exploring, of course, is the long shadow over the talents and accomplishments of women, not only in the arts, but in every field and walk of life. From Artemisia Gentileschi to Hilma af Klint, from Clara Peeters to Fidelia Bridges and Gertrude Abercrombie, hardly a month goes by that doesn’t reveal a “forgotten” woman artist. And that’s just in the plastic arts. Consider Florence Price in music, Anna Kavan in literature—I could go on.

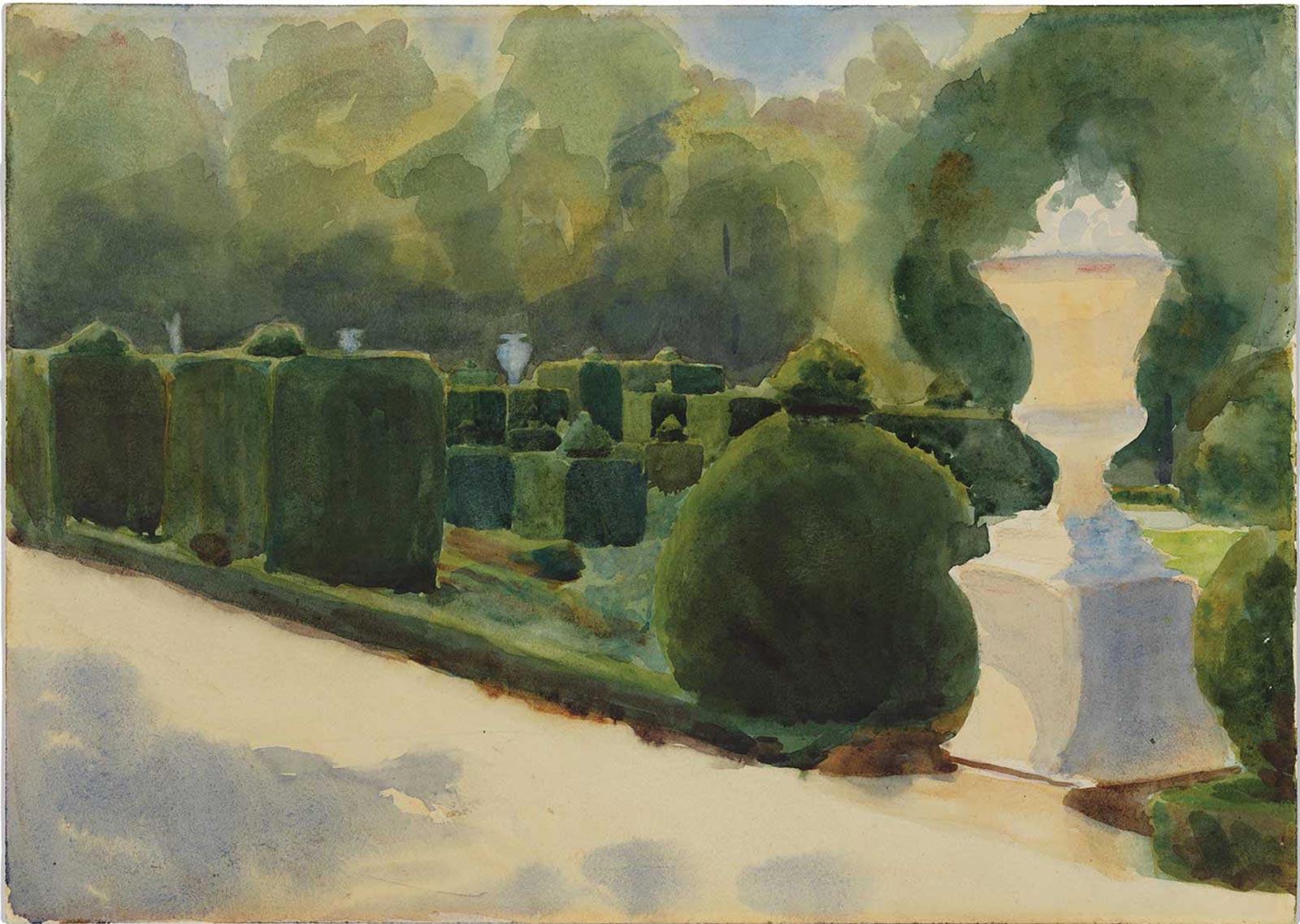

Emily Sargent (1857-1936), Garden Scene with Building, Villa Varramista, 1908. Watercolor, graphite, and wax resist on paper 14 x 20 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous gift, at the request of members of the artist’s family, 2021 (2021.110.11).

In her 1929 essay, “A Room of One’s Own,” Virginia Woolf wrote, “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman,” a quote that has now evolved into the following: “For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.” But the truth Woolf spoke doesn’t quite address the issue. None of the artists I listed above were anonymous. Some of them were quite well known in their lifetimes. Emily Sargent was not anonymous. Is it that art history is a male bastion? It always was. If it isn’t so much anymore it’s due to cultural shifts that have made cultural life, the arts and humanities, into “entertainment,” something that wealthy people—the something that wealthy people—the kind John Singer Sargent painted—patronize (there’s an interesting word) for fun once they’ve made their fortunes.

Looking back, there are parallels in the arts themselves. Not so long ago, it was thought—by men—that women could be taught to paint, and even to sell art in certain, specific subjects: florals, botanicals and other still lifes, in particular, genres that crossed over into decorative arts. “Could be taught to.” See that construction? That passive verb? The dot, dot, dot goes like this: “Could be taught to by men.” Women transformed those genres, made them their own.

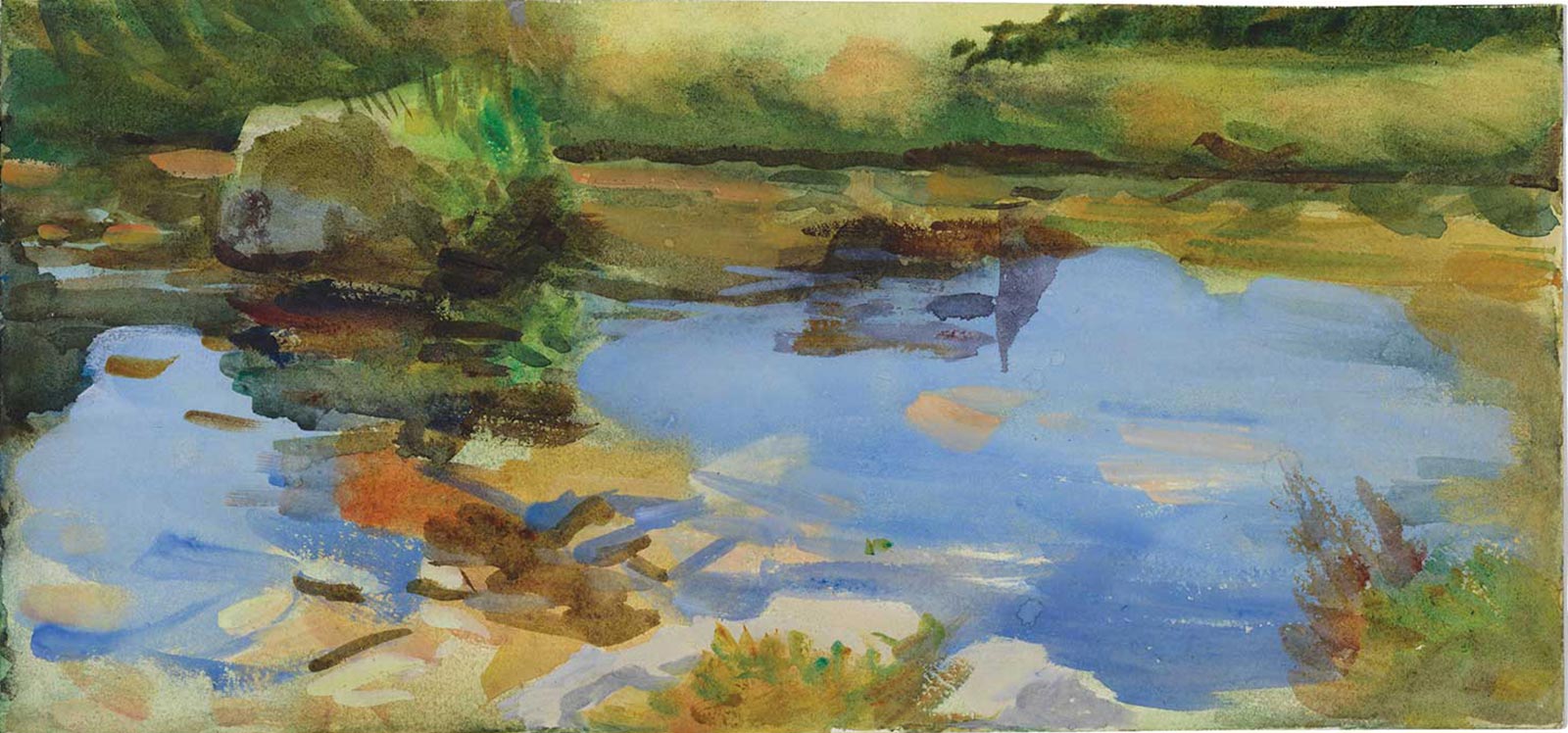

Emily Sargent (1857-1936) and John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) The Brook, Purtud, 1906-08. Watercolor 10 x 14 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous gift, at the request of members of the artist’s family, 2021 (2021.110.1).

So, it’s the latter half of the 19th century. The Sargents have some pretty talented offspring. John, the male, gets the funding, the education, the career, the accolades, the legacy. Yes, there are decades after his death when his work is not in vogue. Still, as American painters go, he’s up there. People are still talking about Madame X. Nothing against John Singer Sargent, but against this backdrop of American art—and American success—Emily paints. Just paints. Wherever she goes, she paints. We might say, “Meanwhile, Emily Sargent paints.” There’s something to be said for this, for making art without ever having to worry about selling it: experimentation never devolves into enterprise. This may seem very private, but, in fact, it’s very public, very open. Art that is made without the spectral duress of the market is simultaneously for the artist and for anyone and everyone, even if no one sees it. Sketches—and we might call Emily Sargent’s work sketches—are always brave and tentative, filled with ideas that are rushed and unhurried, finished and unfinished.

Looking at Emily Sargent’s watercolors in themselves and then against John Singer’s, the feeling is eerie, a sort of doppelgänger feeling that leaves me wondering when Emily schooled her brother and when, exactly, he schooled her. As artists, they are clearly fraternal twins. Not identical. Not identical at all.

Emily Sargent (1857-1936), Avila, ca. 1900-1910. Watercolor and opaque watercolor on paper 10 x 14 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous gift, at the request of members of the artist’s family, 2021 (2021.110.18).

Emily Sargent (1857-1936), Sea with Boat & Figure, Pride’s Crossing, 1923. Watercolor and opaque watercolor on paper, 10 x 14 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous gift, at the request of members of the artist’s family, 2021 (2021.110.25).

If Emily’s watercolor Alhambra and John Singer’s Spanish Midday, Arranjuez, almost certainly painted when they were in Spain together in 1903, have congruencies in terms of palette and, perhaps, the treatment of trees, the deliberate heaviness of line in Emily’s steps and other architectural details as compared to the lightness of line in similar elements in her brother’s painting suggest John Singer’s academic training as opposed to Emily’s largely self-taught plein air directness. Emily’s 1902 watercolor Park Scene, by contrast, is a work John Singer Sargent could and would not have painted. Through point of view and a severely restrained palette, Emily reduces all the natural and architectural elements to geometric forms—cubes, in particular—that relate to one another with mathematical precision. It isn’t Cezanne, but Cezanne would have appreciated it.

By 1908, in Garden Scene with Building, Villa Varramista, a work that mixes watercolor, graphite and wax resist, Emily lets light and rhythm dictate her facture and the resulting painting feels like collage without assemblage; it’s almost as if she tossed brilliant color onto what is, underneath, an abstraction of forms in the darker hues of the natural world. With a translucent gray triangle and a few brown strokes, she manages to create the illusion of a distant hill. John Sloan? John Marin? Maybe. But not until years later. Fifteen years later, in 1923, in Sea with Boat & Figure, Pride’s Crossing, Emily dribbles some white gouache across a watercolor and makes waves. Her figures however, as well as the sailboat in the water, have a very mid-century spikiness to them, something I cannot recall in her brother’s work.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), In the Generalife, 1912. Watercolor, wax crayon, and graphite on white wove paper, 14¾ x 177⁄8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1915 (15.142.8).

One work by John Singer Sargent, In the Generalife, shows Emily at work in the gardens of the Generalife palace at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. Fellow artist Jane Emmet de Glehn is at left, chin in hand, watching her friend and frequent traveling companion paint while another woman, Dolores Carmona, a friend of John Singer’s, sits in the shade at right, also watching.

The famous man watches and paints his talented sister at the easel while one of her friends, an older woman, and a second woman, also a painter, watches her paint. Swirling around the stillness and concentration, the squiggles, the patterns made by light through the leaves, and the mysterious, chalky concentric circles—terrazzo stones?—at right suggest—what? Difficult to say. To hazard, at great hazard, a guess, the world John Singer Sargent knew in his success, a wide, swirling world, is watching Emily as well. Keeping its distance so as not to disturb her, but watching. Maybe with a little envy.

Emily Sargent (1857-1936), Park Scene, 1902. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 10 x 14 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous gift, at the request of members of the artist’s family, 2021 (2021.110.17).

At the risk of actually having an opinion, Emily Sargent: Portrait of a Family sheds more new light on John Singer’s work than exhibitions of the works by the man himself. So, next, I want to see an exhibition of mom’s art, of the art of Mary Newbold Sargent. And then I want to see an exhibition of the artist who appears over Emily’s shoulder, Jane Emmet de Glehn. I looked her up. She is one of 14 women artists in five generations of Emmets. There was an exhibition in 2007—which I wish I’d known about. Time to name more of the anonymous and remember the forgotten. And name them and remember them. Again and again. Time to open all the trunks in the attics and cellars. —

Through March 9, 2026

Emily Sargent: Portrait of a Family

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10028 t: (212) 535-7710 www.metmuseum.org

Powered by Froala Editor