The late pulp illustrator Mort Künstler, who started painting for gritty men’s adventure magazines in the 1950s, created thousands of pieces of art for publications such as Argosy, True and Male. Decades later, he questioned where they all went. “I just think of all those images for all those years. I got a lot of them back, but so many others ended up in closets, or stuffed under a desk somewhere. I’m certain some got tossed on the heap,” he says. “A lot of art by a lot of great artists probably ended up in a bonfire.”

Vernon Court’s Grand Salon inside the National Museum of American Illustration.

For Künstler and countless other illustrators from throughout the 20th century, the final product was not the painting. The final product was a book or a magazine, or even a cereal box or movie poster. Once the client had the image, the painting was an obsolete byproduct of the complex system that financed its creation. Fine art went to museums, and illustration went somewhere else.

Few could have foreseen the shift in that way of thinking, but Judy Goffman Cutler was one of them. In the 1970s, after stumbling into the art world in her mother-in-law’s basement, Judy became a key dealer and collector of American illustration, including artwork from the Golden Age of Illustration, which was a fascinating window of productivity from the late 1800s to (depending on who you ask) sometime around the Great Depression. She remembers those early days when she was starting out and looking at Norman Rockwell paintings priced at $5,000. Today the auction record for Rockwell is $46 million, a number that still shocks her (and would likely shock Rockwell, too). “They would say [that] if you were paid to do something, it was tainted by commerce,” Judy says of the illustrators and the stigma that followed their profession. She adds that time has served them well, and today she feels obligated to teach people how to look at art in a new way. “I tell people, use your eyes to choose if you like it or not…You don’t need an art critic to say, ‘This is art and that isn’t art.’ What’s the difference between an illustrator and a fine artist?…At the end of the day, it’s the illustrator who can pay for his lunch. The fine artists are starving and that’s how they die, and then they become famous.”

N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), The Doryman, 1933. Oil on canvas, 42 x 35 in., signed lower right. For Trending Into Maine, by Kenneth Roberts, Little Brown and Company, 1944.

Judy has strong feelings about illustration, which is what should be expected from the founder of the National Museum of American Illustration. Her museum is located in Newport, Rhode Island, within a grand and stately manor that is an American version of an 18th-century French château. It even has a grand and stately name: Vernon Court. The museum was founded in 1998, but Judy’s art journey begins nearly three decades before that. Her break came when many big breaks happen: in a moment of financial turmoil and desperation.

“My husband was trying to be a builder and he wasn’t really making any money. So we were always borrowing money and we had huge debt with his projects. And I was just trying to think, what can I do and how can I help…My mother-in-law invited me over one night and said, ‘Why don’t you go look in the basement and see what you can find?’” Judy remembers thinking she was going to find an old piece of furniture she could refinish and turn a profit on. “In the back of the basement, I find this dusty print and I didn’t know what it was. I had no idea it was an etching. It was a wedding gift to my in-laws in the ’30s and it was extremely risqué. It was Casanova by Louis Icart, the French artist. It was a wedding gift, but they never hung it in their house, so I took it home.”

Judy Goffman Cutler, the co-founder of National Museum of American Illustration.

After doing some research on Icart and Casanova, the subject of which beckons a disrobing woman into his waiting bed, Judy started finding more Icart etchings at flea markets. With her collection growing, she even placed an ad in the newspaper looking for Icart works. When she visited her parents in Connecticut she found a grouping of them that expanded her collection further. “No one cared about them because they were kind of passé,” she says. “I was just going to try to get them and then I’d figure out what to do with them. I never really had a plan. I could always trade them for duplicates, or go to flea markets and sell them. I’m a good negotiator, so let’s see what I can do.”

When she read about an Icart exhibition, she called the show’s sponsor, who told her the exhibition was cancelled because his Icart loans had been pulled. “He told me, ‘I have no inventory. Do you have any?’ Well, I had a couple, maybe 25,” Judy remembers, adding that the sponsor quickly offered to buy them all. “I thought about it and it didn’t last too long—I said yes, but I wanted $10,000.” And that’s how an art dealer was born.

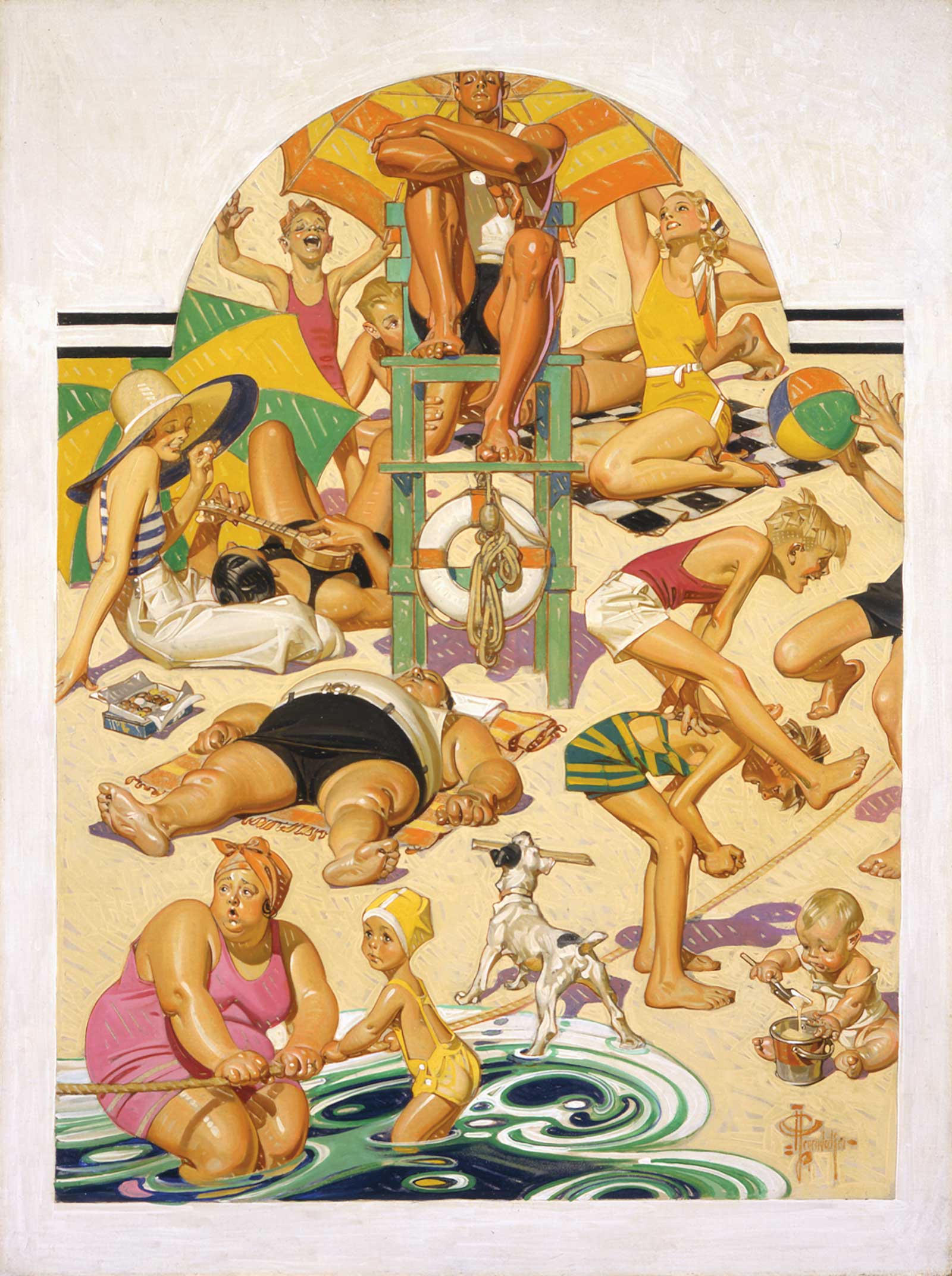

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), Labor Day at the Beach, 1932. Oil on canvas, 32 x 24 in. For Saturday Evening Post, September 3, 1932, cover.

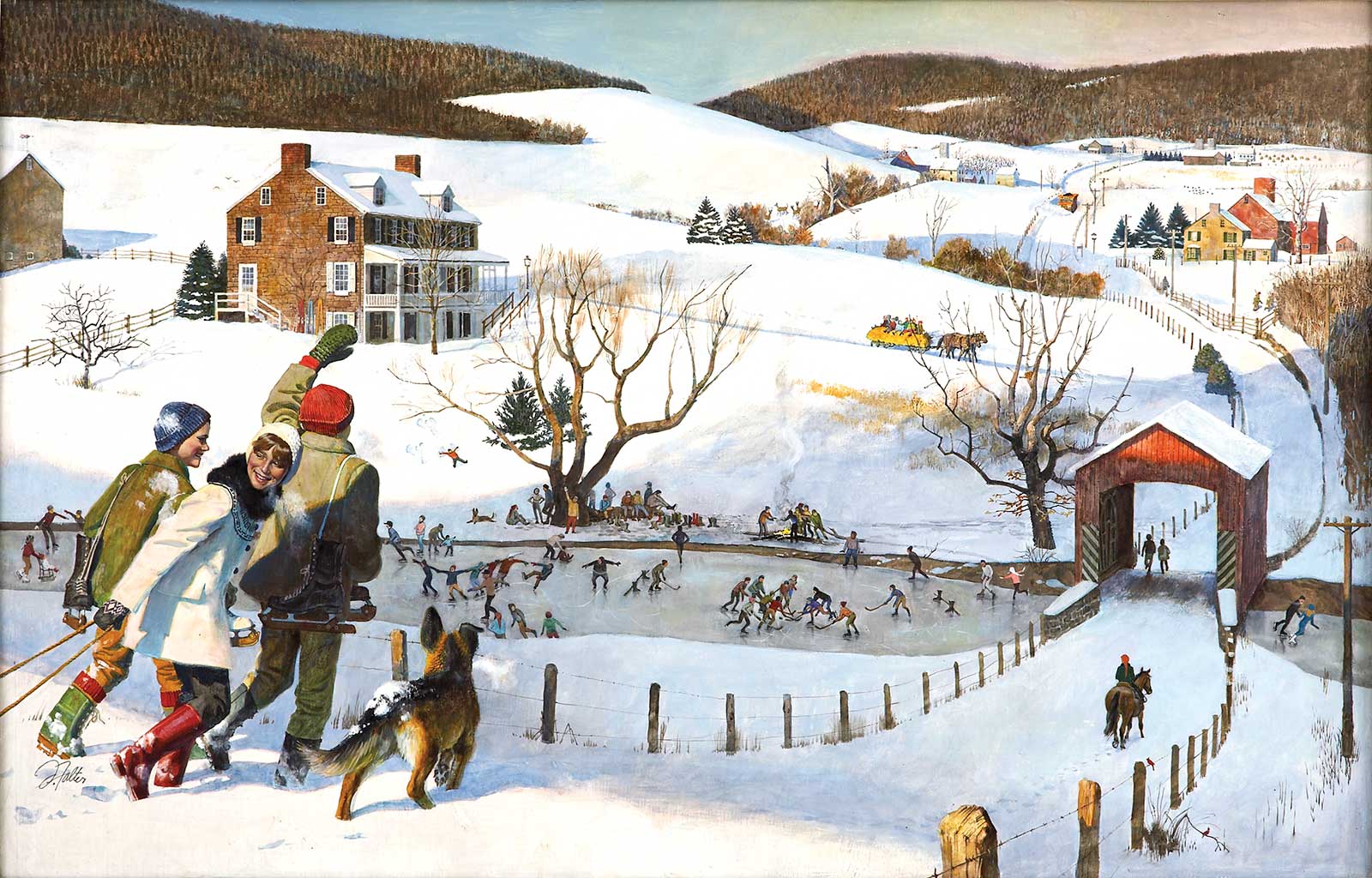

John Falter (1910-1982), Winter Fun in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1971. Oil on canvas, 27 x 42 in., signed lower left. For Saturday Evening Post, Winter 1971 double-page cover.

With the Icart money, she bought a Max Weber painting for $7,500, a painting she still has today, and then some other paintings with the remaining $2,500. By the mid-1970s she was interested in Howard Chandler Christy, Charles Gibson and James Montgomery Flagg, all of whom led her deeper into American illustration. Judy fondly recalls an episode in which she bought a painting from Christy’s estate and studio featuring his model and student Elise Ford, who Christy had been having an affair with late in his life. Mrs. Christy refused to let him finish the painting, so it was stored under a bed. Judy bought it for $50.

Although these ventures were successful, her forays into the art of Gibson, Christy and Flagg were just warm-ups of what was still to come. She had been told to look into the work of Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker, both prominent cover artists for the Saturday Evening Post. “I knew Rockwell, but I couldn’t afford Rockwell. They go for $5,000. That was like mana from heaven—$5,000,” she says. Today, $5,000 can barely buy a signed Rockwell letter or miniature sketch.

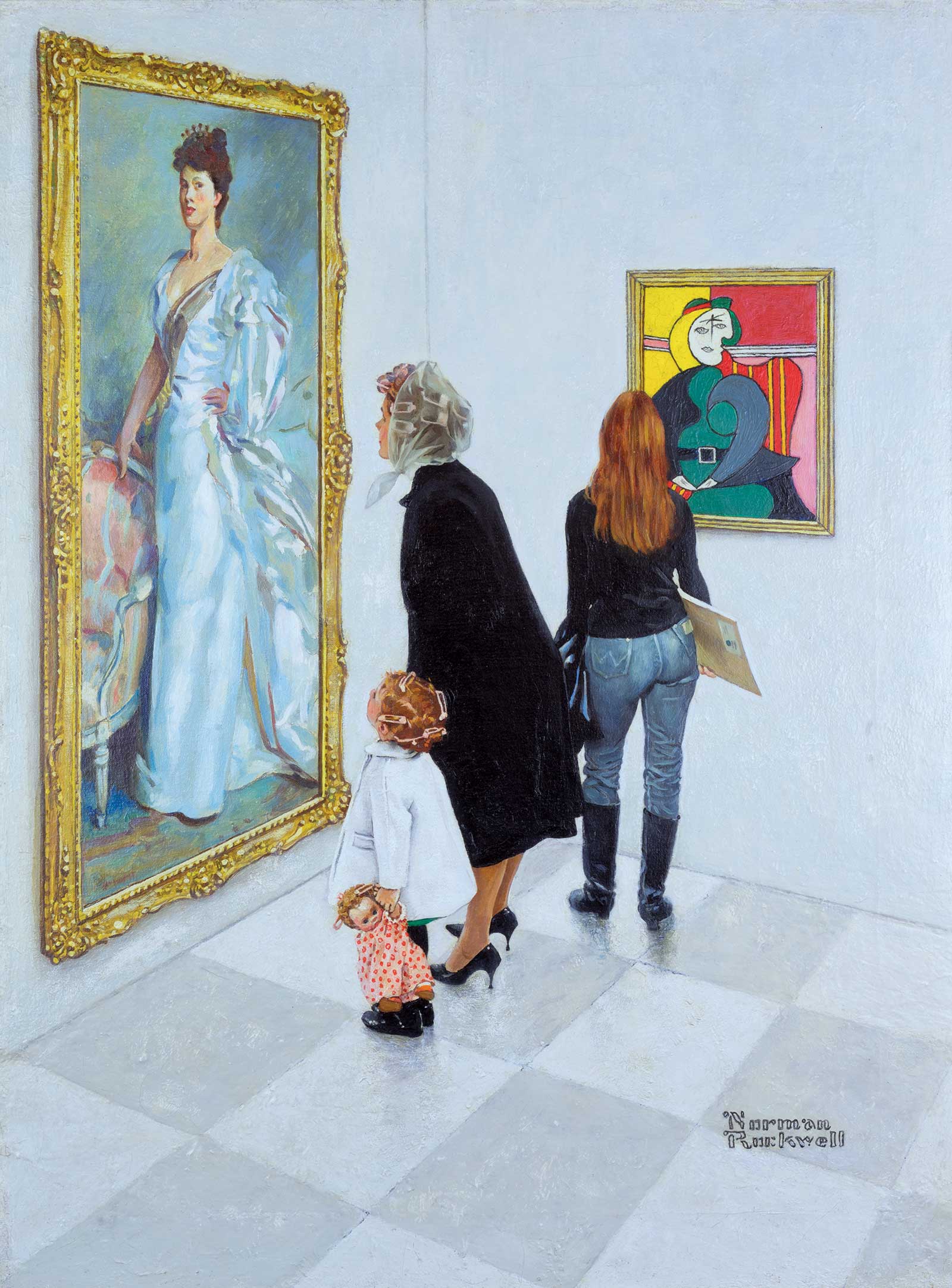

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), Picasso vs. Sargent, 1966. Oil on canvas, 22 x 17 in., signed lower right. For Look Magazine, January 11, 1966, pg. 25.

But Rockwell and Leyendecker led Judy backward through art history to Howard Pyle, the grandfather of American illustration. Pyle’s fingerprints were all over the genre, first at Philadelphia’s Drexel Institute in 1894 and then later at his own school, the Brandywine School of Illustration Art, near his hometown of Wilmington, Delaware. The school would create many of the early stars of American illustration: Harvey Dunn, Philip R. Goodwin, Elizabeth Shippen Green, W.H.D. Koerner, Violet Oakley, Maxfield Parrish, Frank Schoonover, Jessie Willcox Smith, C. Leslie Thrasher and, certainly the most famous among them, N.C. Wyeth.

She likes to point out how influential the school was on several key fronts: First, it taught a significant number women artists, many of whom were shut out of other artistic fields; second, the school put artists to work and got them paid, a blue-collar alternative to the struggle that came from the fine art side of the market; and third, the art was accessible to a huge segment of Americans, essentially anyone who could afford a magazine or book.

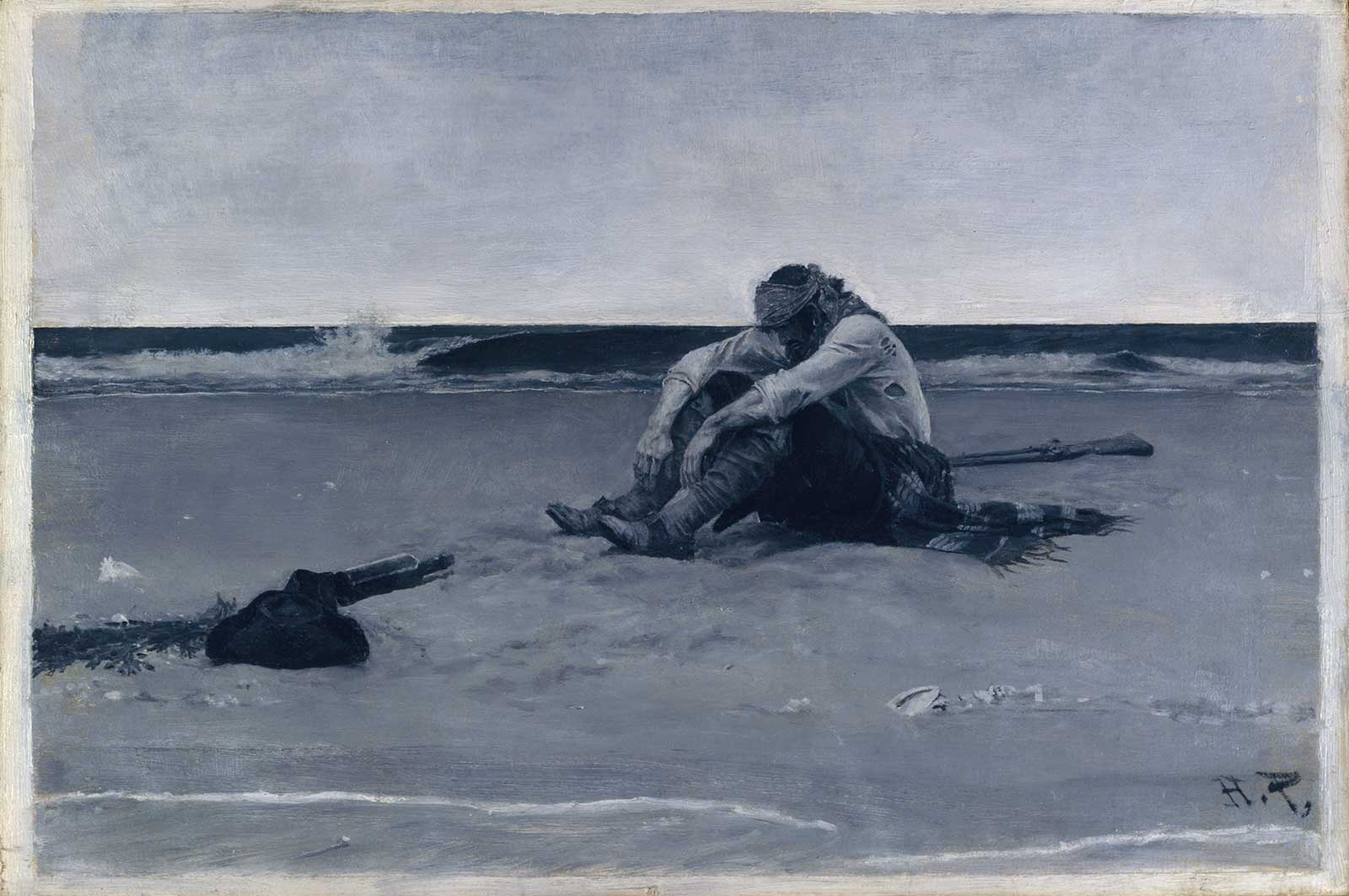

Howard Pyle (1853-1911), Marooned, 1887. Oil on board, 16 x 23 in., signed lower right. For “Buccaneers and Marooners of the Spanish Main” by Howard Pyle, Harper’s New Monthly, August/September 1887.

Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), Little Miss Muffet, 1912. Oil on board, 18 x 25½ in., signed lower right. For Good Housekeeping Magazine, January 1913, and The Jessie Willcox Smith Mother Goose, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1914.

And yet, as influential as Pyle and his students were, American illustration languished (at least in prices) behind impressionism, modern art and other movements. “[Once the works were painted] they all kind of went their different ways, but they had no intrinsic value. People bought them, but just because they liked them. Or they ended up with people who inherited them and didn’t want them. It was working out perfectly for me because these artists had fallen into disfavor. I wanted the dead artists because I could reinvent them. I could talk about them. Because nobody else valued them, I at least could buy them and I could afford them, and then I could improve them and…make a case for why they were important,” Judy says, adding that illustration is part of our culture, whether it’s Wyeth’s Treasure Island illustrations or Rockwell’s covers for the Saturday Evening Post or Pyle’s influential paintings of pirates. She wants the center of the genre to be at the National Museum of American Illustration, and it largely is with a world-class collection in a stunning venue.

For Judy, the icing on the cake is that the art market has finally caught up to her vision of what American illustration is worth. One doesn’t have to look hard to find six- and seven-digit sales records for Wyeth, Pyle, Schoonover, Dean Cornwell, Leyendecker, Parrish, Dunn, Goodwin and many others. “That was my validation. I mean, it’s a shame that money awakens people’s interest more than the art, but at least it’s a vindication in that the art finally is respected and finally included in the canon,” she says. “…It’s really wonderful to see that interest.”

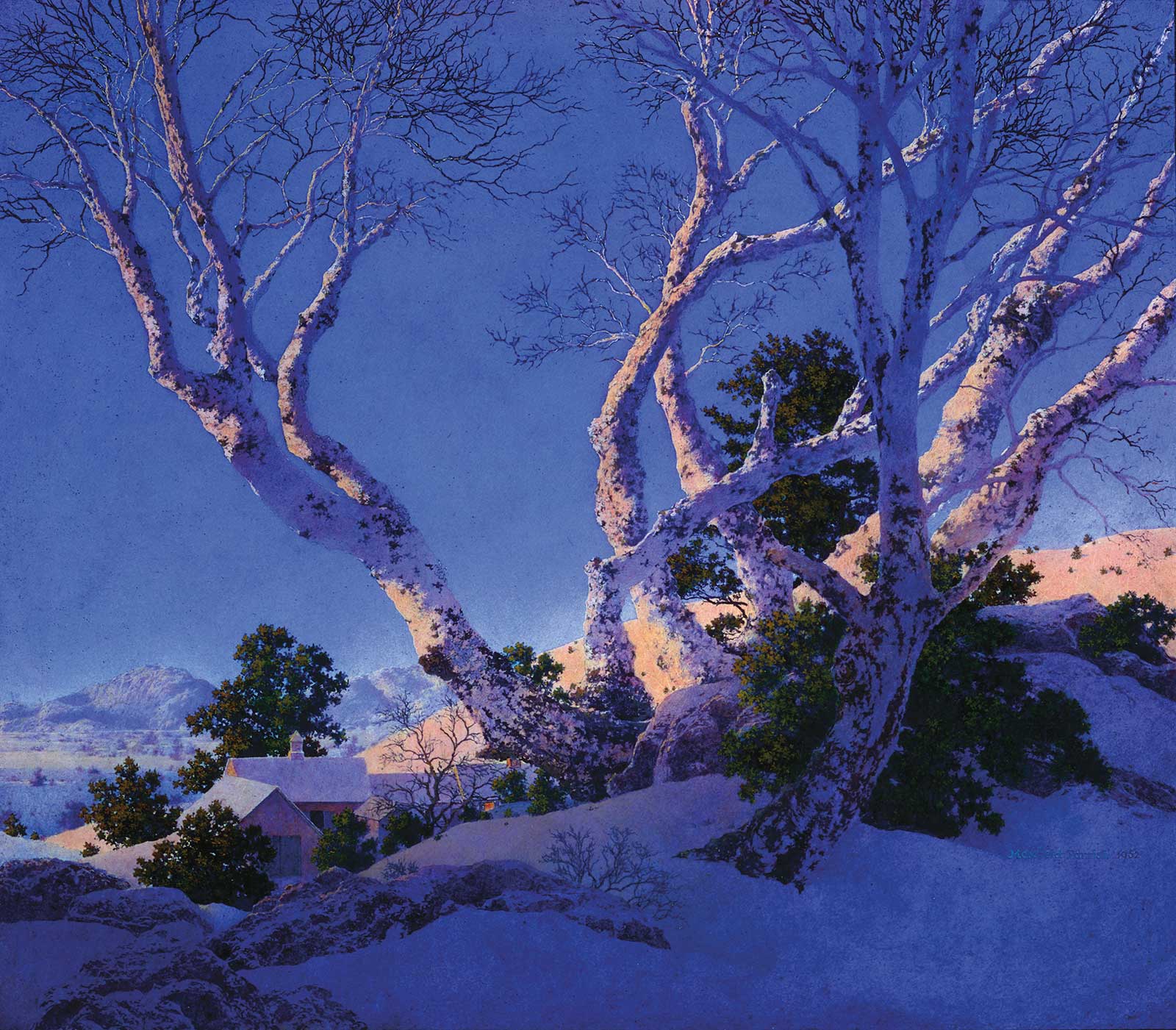

Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966), Sunrise – White Birches in a Glow, 1915. Oil on Masonite, 13½ x 15½ in., signed and dated lower right. For Brown & Bigelow Executive Print, 1955. All images courtesy National Museum of American Illustration. © 2025 National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI, www.americanillustration.org, and the American Illustrators Gallery, New York, NY, www.americanillustrators.com.

Not only is the museum home to a stunning collection, but it also hosts exhibitions and special events. Currently on view are Gilded Age Splendor in Golden Age Illustration, which examines a 50-year period of wealth and economic growth through the lens of illustration, and The Influencers of the Golden Age of Illustration, which pairs historic illustrators with present-day artists who were influenced by their works.

“When people walk in, they’re spellbound,” Judy says. “Because you can’t imagine the impact of these works.” —

The museum is open by appointment. Learn more at www.americanillustration.org.

Powered by Froala Editor