The American Scene was a realist art movement born out of a response to the Great Depression and the shockwaves it sent throughout the nation, upsetting rural and urban lives alike, and evoking trepidation about geopolitical issues at home and abroad. Encompassing regionalism and social realism, American scene paintings rejected abstraction, but not necessarily modernism, in favor of depictions of everyday life and the landscape with an emphasis on narrative and national identity.

Dale Nichols (1904-1995), RFD #1, 1937. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in.

Through October 15, CW American Modernism will present The American Scene: Visions of a Nation, a selection of 30 paintings from the 1930s and ‘40s that provide a visual window into this tumultuous time in our country’s history.

Regionalism, which tends to be more nostalgic and concerned with rural America than social realism, is represented by artists Dale Nichols, William Ashby McCloy, Roger Medearis, Martin Murray, Ann Kutka McCosh, William C. Palmer and Dorothy Varian. In the category of social realism, which often took a critical view of American society, especially urban issues related to poverty, labor and loss, are paintings by Reginald Marsh, Louis Goodman Ferstadt, Mildred Olmes, Bernice Perry Sutton, Norman Barr and Cecil Bell.

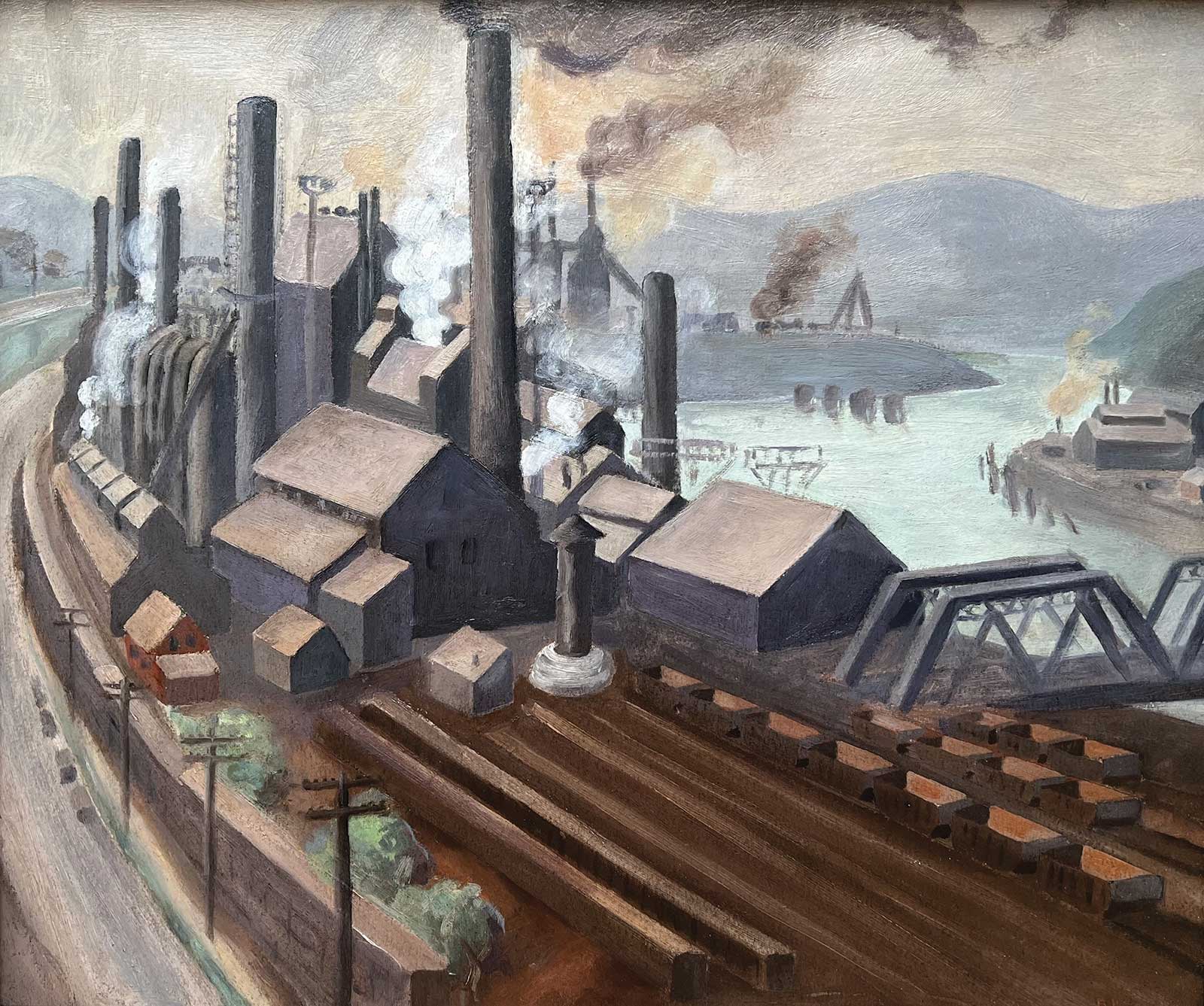

Bernice Perry Sutton (1908-1977), Jones & Laughlin Mills (Untitled), 1934. Oil on panel, 20 x 24 in.

“No other time in U.S. history had American artists been so focused on depicting not only the American landscape, but also American culture, values, practices and daily life,” says gallerist Chris Walther. “The approach was extraordinarily widespread from large cities to rural towns and hamlets. Few subjects of the quotidian were off limits and depictions were often local and specific from New York to California and everywhere in between. The American Scene attempted to capture—sometimes glorify and sometimes condemn—that which was symbolically American from the factories of the Rust Belt to the farms of the rural Midwest.”

In Sutton’s Jones & Laughlin Mills (Untitled) we have an example indicative of the urban alienation many felt in response to the rapid industrialization that was transforming the outer and inner landscapes. Dale Nichols’ RFD #1, on the other hand, exemplifies Nichols’ regionalist style, but goes beyond his idealized portrayals of Nebraska farms with the inclusion of a mail carrier automobile, another symbol of the changing times.

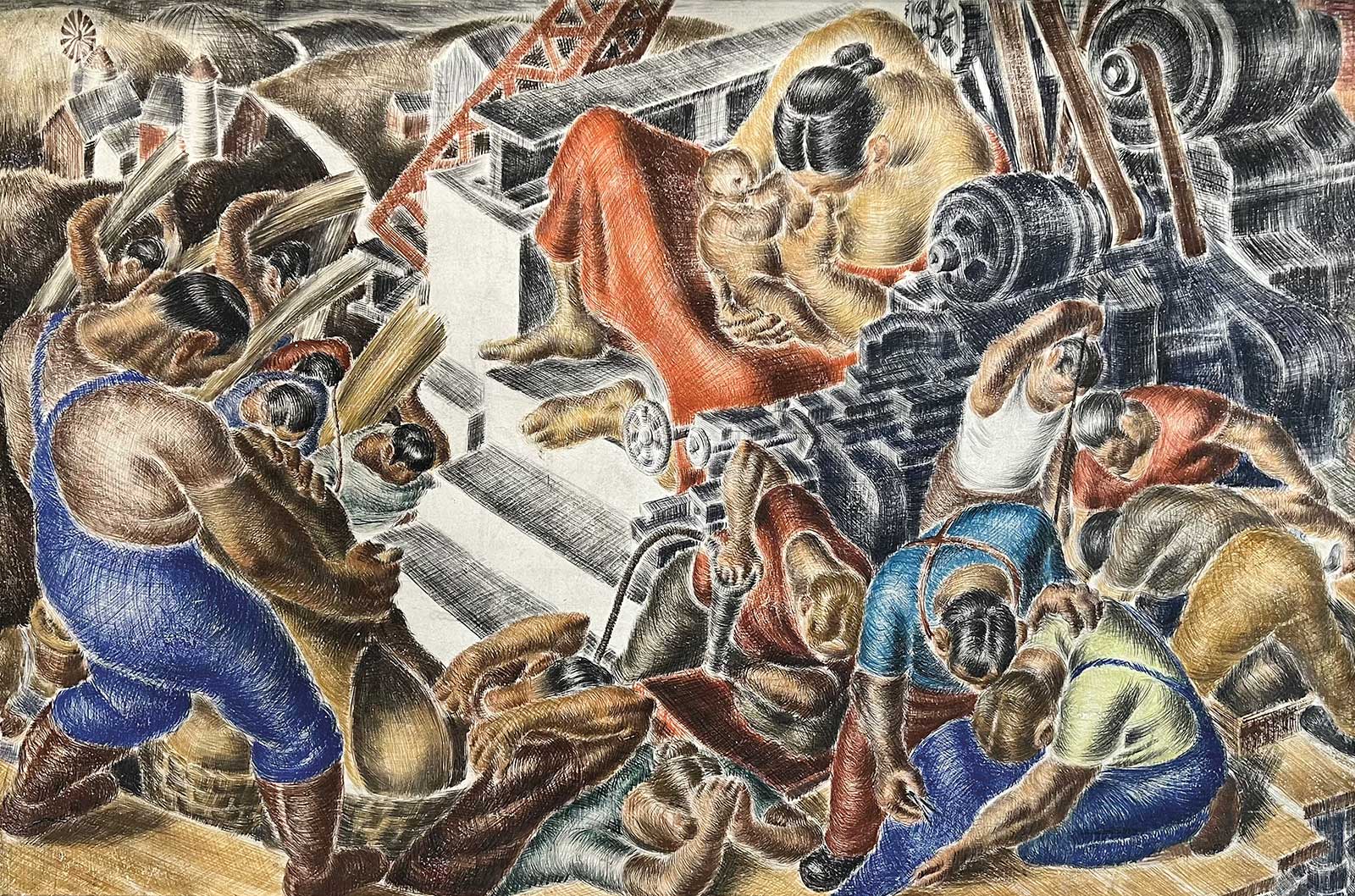

Louis Goodman Ferstadt (1900-1954), Farm Tragedy (Untitled), ca. 1930s. Mixed media on plaster on panel, 221⁄8 x 32 in.

Cecil Bell (1906-1970), World War II Invades Central Park, 1943. Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 in.

Walther also points to McCloy’s Self Portrait as a prime example of regionalist art. The painter and muralist worked with noted Kansas regionalist John Steuart Curry. “McCloy’s regionalist style featured clear draftsmanship, bold contours and simplified yet expressive forms, often with a cinematic quality which is evident in Self Portrait,” explains Walther. “McCloy positions himself against a swirling, elemental backdrop suggestive of the natural forces of his native Midwest but rendered with psychological intensity. His long, sinewy hands and introspective gaze convey both creative tension and emotional restraint. The regionalist influence is evident in the textured, expressive treatment of the background, evoking a connection to rural life and the American landscape. The turbulent energy which surrounds the artist contrasts with his own stillness, perhaps underscoring an internal struggle as well as the tumult of the Great Depression itself.”

Ferstadt’s Farm Tragedy, likely a study for a mural, is another standout among the works of social realism. Ferstadt painted significant murals at the RCA Building and the Eighth Street Subway station in New York City in connection with the 1939 World’s Fair, and was active in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop and the Mural Artists Guild, advocating for artists’ rights. “His art often depicted social themes, combining abstraction with classical realism and adopted uncommon stylistic approaches such as neo-pointillism and graphic cross-hatching, as in the case of the present work,” says Walther. With its modernist depictions of workers, machinery and the stylized constructed environment, Farm Tragedy (Untitled) is a prime example of Ferstadt’s social realist work from the inter-war period.

William Palmer (1906-1987), Indolent Interlude, 1936. Oil on board, 12 x 16 in.

Martin J. Murray (1908-1997), High School Freshman, 1948. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 in.

“The American Scene reflected back a wide array of aspects of American society,” explains Walther, a cross-section of which can be seen in The American Scene. “Whether depicting the construction of a New York City subway; an aspirational, though uncertain young man, contemplating his future; an industrial accident; a relaxed seaside escape or a scene of sailors in New York City, all of the works in The American Scene: Visions of a Nation tell us something about an America that is now irretrievably past, but still nevertheless relevant to our world today—something inspiring and something challenging. Because of both government and corporate support, the art of the American scene was widely available and widely published, making the works from this period well known and often well regarded. The narrative and immediately recognizable quality of many of the paintings of this period allowed viewers to identify easily with the images and the messages conveyed.”

The American Scene: Visions of a Nation can be viewed online at www.cwamericanmodernism.com or in person at the Los Angeles gallery by appointment. —

Powered by Froala Editor