The Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, houses the world’s largest collection of watercolors by the master of the medium, Winslow Homer (1836-1910). The exhibition Of Light and Air: Winslow Homer in Watercolor brings together dozens of his watercolors and related oils, drawings and prints for the first time in nearly 50 years. It opens November 2 and runs through January 19, 2026.

Both the museum’s director, Pierre Terjanian, and its curator of prints and drawings and co-curator of the exhibition, Christina Michelon, refer to the fragility of the watercolor medium in the book accompanying the exhibition. Ethan Lasser, chair of art of the Americas, is co-curator.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), The Blue Boat, 1892. Watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, sheet: 153⁄16 x 21½ in. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Terjanian explains, “Since its establishment over a century and a half ago, the museum has cared for and preserved fragile works of art for future generations. Homer’s iconic watercolor The Blue Boat, a favorite among art lovers around the world, remains nearly as vibrant as the day Homer painted it. Watercolor is extremely sensitive to light, which limits how often these precious pictures can be displayed in our galleries.”

Michelon observes, “Watercolor, pioneered by Homer as a medium for capturing the ephemeral, can be materially ephemeral itself. Extremely sensitive to light, watercolor’s fugitive pigments can disappear under the wrong circumstances. Remarkably, Leaping Trout remains nearly as vibrant as Homer intended, likely because it was safely housed in museum storage the majority of its life. One of the finest examples of Homer’s skill in the medium, Leaping Trout was the first Homer watercolor to be purchased by a museum.”

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Driftwood, 1909. Oil on canvas, 24½ x 28½ in. Henry H. and Zoe Oliver Sherman Fund and other funds. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

As a frequent visitor to the MFA for most of my life, I’m among the many who cherish The Blue Boat and his other paintings of the Adirondacks. I had never seen Leaping Trout, which is coming close to replacing The Blue Boat at the top of my list of favorite Homer watercolors.

Michelon offers insights into Homer’s work beyond the representational. “In contrast to the grand narratives in his later oil paintings, Homer’s watercolors are rooted in the moment and the surface effects of light. Though often ambiguous, they are not without symbolism. In the numerous representations of leaping fish done throughout his career, Homer illustrated both real insects and artificial lures. In Leaping Trout, it is unclear if the mayfly is real or fake, underscoring the art of artifice inherent in both Homer’s painting and in the act of fishing itself. Mayflies—the object of the trout’s acrobatic efforts—only live for about 24 hours and have been deployed as a metaphor for ephemerality by artists for centuries. Thematically and compositionally, this watercolor also evinces Homer’s fascination with life and death. The pairing of twin bodies mid-air is reminiscent of Homer’s late oil painting Right and Left. Finished a year before the artist’s death and depicting a hunter taking aim at the two birds in the foreground, the painting is rife with references to mortality. However, Leaping Trout’s narrative is more enigmatic: are the fish predators or prey?”

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Driving Cows to Pasture, 1879. Watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, sheet: 89⁄16 x 139⁄16 in. Bequest of Katharine Dexter McCormick. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The title of the exhibition comes from a quotation by the author and critic Henry James who wrote, in 1875, “Mr. Homer has the great merit, moreover, that he naturally sees everything at one with its envelope of light and air. He sees not in lines, but in masses…Things come already modelled to his eye.”

James was also capable of harsh criticism of the artist. From the peak of his ivory tower he wrote, with backhanded praise, that Homer’s work was “almost barbarously simple, and, to our eye, he is horribly ugly…He has chosen the least pictorial features of the least pictorial range of scenery and civilization as if they were every inch as good as Capri or Tangier; and, to reward his audacity, he has incontestably succeeded.” Later he described Homer’s children as “freckled, straight-haired Yankee urchins” with their “calico sunbonnets and flannel shirts.”

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Boys in a Pasture, 1874. Oil on canvas, 157⁄8 x 227⁄8 in. The Hayden Collection—Charles Henry Hayden Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The exhibition contains drawings and paintings of his “urchins” engaged in the simple pleasures of nature in fields and on the sea. One of my favorite urchin paintings is the oil, Boys in a Pasture, reminiscent of my childhood summers on a farm in New Hampshire and, much later, sitting with friends on the hill in front of the Olsen House in Cushing, Maine, made famous by Andrew Wyeth, eating wild blueberries and raspberries.

Michelon explains, “A lifelong admirer of the outdoors and keenly aware of contemporary tastes, Homer continued to center carefree children, industrious youths, wistful maidens, and laboring farmhands in his work from the late 1860s and 1870s. Boys in a Pasture is a prime example of his work from this era and also of the relationship between his painting in oil and his painting in watercolor…Homer also applied bright white highlights to the nearest boy’s shirt to evoke illumination by bright sunlight.”

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), The Adirondack Guide, 1894. Watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, sheet: 153⁄16 x 21½ in. Bequest of Mrs. Alma H. Wadleigh. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), The Lookout—”All’s Well,” 1896. Oil on canvas, 397⁄8 x 301⁄8 in. Warren Collection—William Wilkins Warren Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

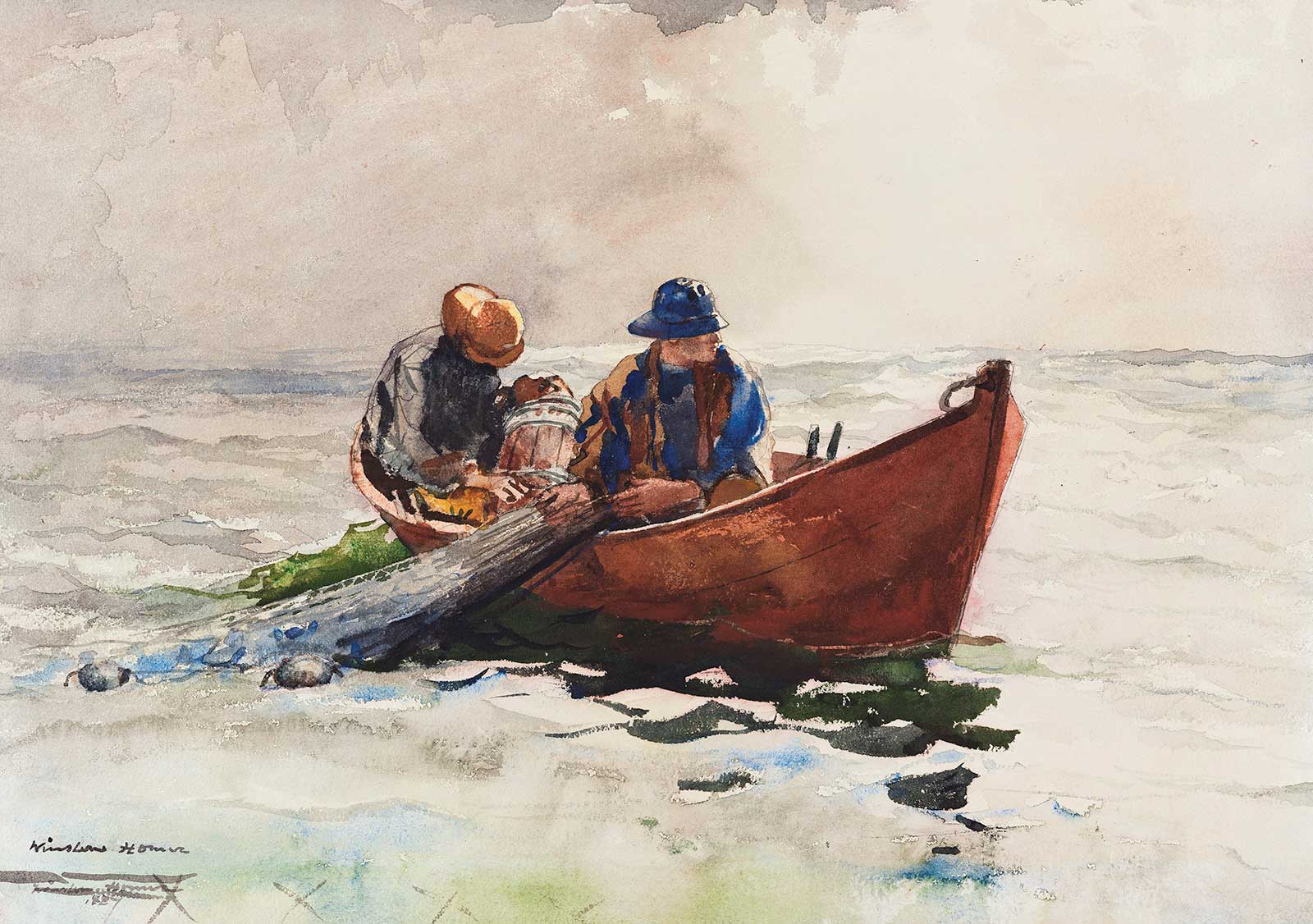

His technique in watercolor is described by Annette Manick, head of paper conservation at the MFA. “By the late 1870s, Homer’s watercolor practice began to evolve and embrace features unique to the medium, moving from rigid and opaque to fluid and transparent. Driving Cows to Pasture stands out as a turning point for Homer’s work in the medium and evinces a more conscious shift to landscape from figure study. The boy in the foreground is a departure from the models of previous posed works. With his back turned to the viewer, he assumes the pose of a rückenfigur (a figure seen from behind), a compositional device that Homer would return to in later works (see Driftwood, for example). The boy, seemingly rooted to the ground, is nearly consumed by unruly flora. Walking stick in hand, the boy seems the youthful counterpart to the central figure in Homer’s later The Guide and Woodsman, while the immersive landscape presages that of his later masterwork The Blue Boat. The cows, rendered as brown blobs on the hillside, would be easily missed were it not for the title. Here, Homer embraced abstraction as well as some advanced watercolor techniques, removing pigment through scraping and lifting to create rough rocks and ghostly ferns.”

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Leaping Trout, 1899. Watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, sheet: 14 x 20 in. Warren Collection—William Wilkins Warren Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In 1884, Homer’s older brother, Charles, converted and enlarged a garage on his property on Prouts Neck, south of Portland, Maine, for his brother’s home and studio. Manick writes, “Homer worked in his seaside Prouts Neck studio for over 25 years, tirelessly observing the elements and the comings and goings on the water. At one point, Homer wrote “turn, turn, tumble…tumble, tumble, turn…” on the walls of his house, articulating the motion of rolling waves, a phenomenon he frequently strove to capture. In Breaking Wave (Prouts Neck), Homer rendered the swell and spray of the sea against rocks in layers of blue and green, manipulated through blotting to create greater dimensionality. Homer later incorporated a similar crashing wave in his final oil painting, Driftwood.” Driftwood depicts the sea pounding on the rocks below Homer’s studio. Today, visitors can experience the sea in its many moods on visits to the studio booked through the Portland Museum Art.

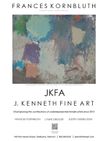

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), The Dory, 1887. Watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, sheet: 15¼ x 215⁄16in. The Hayden Collection—Charles Henry Hayden Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), The Guide and Woodsman (Adirondacks), 1889. Watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, sheet: 14 x 20 in. Bequest of John T. Spaulding. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Homer wrote, “I don’t want a lot of people nosing round my studio and bothering me. I don’t want to see them at all. Let the dealers have all that bother…The life that I have chosen gives me my full hours of enjoyment for the balance of my life: the sun will not rise, or set, without my notice and thanks.” —

November 2, 2025-January 19, 2026

Of Light and Air: Winslow Homer in Watercolor

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

465 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 t: (617) 267-9300, www.mfa.org

Powered by Froala Editor

Powered by Froala Editor